March24,2015

Coming to Honduras for the first time, many things might make you feel uneasy because they are different from the environment your body and brain are accustomed to. But the consciousness of that, just what is different and why it makes you uneasy, lags behind the feeling itself. There are biological reasons for that, but suffice it to say it takes a little time for you to figure out what’s different here. One thing you’ll figure out rather quickly, however, especially if you’re over 30 years old, is that there is a superabundance of young people. Anywhere you go in public, they just seem to swarm about you. It’s pretty easy for your conscious brain to figure that out. The median age of the population here is 20.7 years and the life expectancy 74. In the US, the median age is 36.9 and the life expectancy 79.8. That’s a huge difference. Public and social life is dramatically different here because of it.

Life for adolescents and young adults is much more structured in the US than here. In the US, almost everyone is in school until at least 18 years of age, and a significant proportion continue with higher education. In Honduras, 60% have finished their education by the sixth grade, much fewer attend or graduate high school, and in realty almost no one goes on to higher education. In the US, young people who are not in school are generally in the work force. In Honduras, those who are in the work force are generally pretty young, but work itself is pretty scarce. Besides these two most obvious and striking differences for the socialization and personal development of youth, the countless supports for adolescents and young adults in the US are rare to non-existent here. Here, families and culture are the principle, if not the only, supports for adolescent development. Some families provide this support superbly. But many families are simply too challenged. Mothers are too young, fathers are too distant or not present at all, financial hardships are too demanding, and older siblings take on parenting roles too young. There are already too many young people, their numbers expand exponentially, and all the while the structures and supports to be a healthy, happy young person are shrinking.

Dr. Martha Kubik and the student nursing brigade from the University of Minnesota have been in Southern Intibucá this past week. Their focus, a much needed focus, is adolescent youth. Laura and I met up with them in Camasca at the High School. We were with them in the auditorium where they were seeing fifteen to twenty year olds. Dr. Kubik was very busy organizing the event, but she had a few minutes to speak with me. With a beaming smile she said to me, “Look at these kids, aren’t they wonderful. They’re just like kids in the US.” I have to admit her statement initially threw me. The difference in experience for kids in Honduras and kids in the US is stark. Honduran kids face challenges that, quite frankly in my opinion, no kid should face. But, I had the opportunity to observe the kids gathered in the auditorium and reflect on what she said. First I recognized that what she said was absolutely correct. Second, I realized that she fully appreciates the challenges for Honduran youth and was responding to them justly and with compassion.

There is a universal experience to what it means to be an adolescent. There is a biological component and its consequent expression in socialization. I watched how the kids touched one another, testing and experimenting. I watched their vivid, almost exaggerated, expressions; moved deeply it seems by life’s fullness and its affect on them. They smile widely at one another, but alone, unwatched, deep sadness can cast shadows over that brilliance. Boys tease girls almost ceaselessly. Girls feign annoyance, glaring at them disapprovingly, then turn to their girl friends with knowing pride. They are insatiably curious. All of them questioned the cards they were given by brigade members. Two simple English words, “vitals” and “screening,” were written on the cards indicating the two procedures they were to have. All of them wanted to know what the words meant. The brave ones called me or one of the interpreters over to translate. A very industrious, young man left the auditorium and returned with an English-Spanish dictionary. Unfortunately, it didn’t help. Challenge and discovery, fear and joy, love and rejection intensely fill their days. The world, their futures, are yet unexplored; terrifying demands and limitless opportunities. Whereas if I studied them carefully I could note the subtle cultural and environmental influences on their behavior, this would dishonor the primary influence of their journey. They are discovering who they are and how to be one with another.

Dr. Kubik and the University of Minnesota, after extensive research and focus groups here in Honduras, have designed an interviewing tool to use among adolescent, Honduran youth. First they are weighed, measured for height, and have their blood pressure checked. Then they sit down individually, one on one, to dialogue over a few key themes of how to be a young person. Two of the brigade members were Spanish-speaking, and three were assisted by translators. The interview speaks to nutrition, exercise, sports, socialization, relaxation, and a variety of youth health themes. It also touches upon mental health, sexuality, and drug use. The content is excellent. There is no demand that the young person converse. Some might. Most don’t. But they know that many of the things they’ve been feeling are not a mystery. It’s the normal process of life and socialization. If something is discovered in the process that gives concern for the well-being or the health of the young person, a referral is made.

Dr. Kubik and the University of Minnesota, after extensive research and focus groups here in Honduras, have designed an interviewing tool to use among adolescent, Honduran youth. First they are weighed, measured for height, and have their blood pressure checked. Then they sit down individually, one on one, to dialogue over a few key themes of how to be a young person. Two of the brigade members were Spanish-speaking, and three were assisted by translators. The interview speaks to nutrition, exercise, sports, socialization, relaxation, and a variety of youth health themes. It also touches upon mental health, sexuality, and drug use. The content is excellent. There is no demand that the young person converse. Some might. Most don’t. But they know that many of the things they’ve been feeling are not a mystery. It’s the normal process of life and socialization. If something is discovered in the process that gives concern for the well-being or the health of the young person, a referral is made.

When the interviews were over, I watched the brigade members coming back together with the group. They all displayed a satisfied, even joyful, expression. I asked each of them how it went. They all thought it was meaningful. They all seemed to gain a sense of fulfillment. I imagined that for many of these kids this might be the only time someone has explained some of what they are feeling. How essentially important that is! When we honor someone else’s experience, when we can reflect our common humanity, we are sharing a precious gift. Though there is so much more the kids in Honduras need, without this gift of honoring, we would simply miss the real point of it all.

Thank you Dr. Kubik and all of the Minnesota nursing students for honoring the youth of Honduras.

Thank you Dr. Kubik and all of the Minnesota nursing students for honoring the youth of Honduras.

Not in Wisconsin Anymore…

February 2, 2015

My bias toward Wisconsonian culture is primarily based on the limiting view of crazed Green Bay Packers fans wearing cheese wedge slices as hats. Additionally, as a haughty, New England, right coaster, I lump Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota together. It’s really, really, really cold there, two or three days of summer in August at the most, and anyone purposely living under those conditions is very suspect. There aren’t any cities, everyone is a rural farmer, and the Lutheran Church forms everybody’s moral conscience. I blame the latter on NPR and Garrison Keillor. My bias of Wisconsin provincialism and narrow-mindedness was well-formed until just recently.

In January, Marcia LaSalle, a Milwaukee, Wisconsin native, arrived in Camasca, Intibucá, Honduras to begin four months of volunteer service at the Good Shepherd Bilingual School. Though her surname is French, her father is Puerto Rican. Her home life implied cultural diversity even as her mother, by Marcia’s own description, might have stepped right out of a Leave It To Beaver episode. Marcia visited Puerto Rico and her grandparents in Aguadilla, PR as a child and is close to many family members on her father’s side. Thus, she was acquainted with Spanish, but her father chose not to speak Spanish in the home. Marcia is very proud of her Latina heritage and wished she had learned more Spanish as a child. As a 21 year old adult, she is now becoming fluent in Spanish, having lived and traveled in Spain and now in Honduras. Not at all fearful or timid, seeking to expand her experiential horizon, she studied in England. The Wisconsin world traveler decided to spend the next four months in Honduras after completing the majority of her course requirements at St. Norbert’s College a semester early. When she returns in May she will have her BA in Anthropology.

Apart from that liberal, cosmopolitan, adventure-seeking, Wisconsin spirit, what brought Marcia to Honduras? A childhood friend spent some time here in Honduras with Shoulder to Shoulder. Whereas that had to have been influential, it’s perhaps best understood as presenting her the door to opportunity. Choosing to open that door was not in order to follow her friend, but to sate her own spiritual quest. Marcia witnesses an inner drive to meet and know others outside her own comfort zone. It is no surprise that she majored in anthropology. She admits to a fascination with culture. How is it that we can be so different, and yet so the same, and why? Most of us are content to be with others who act, think, and feel in similar ways. There’s a safety in sameness. But Marcia discovered that the best way to be pulled and challenged, to be self-reflective and to grow, is to feel just a little insecure around persons unlike oneself.

Marcia is at our bilingual school. Though she makes no claims on either being, or wanting to be, a teacher, she is present and sharing with the children. She’s teaching them English as they are helping her to hone her Spanish. They are communicating. More importantly, they are reaching out across culture, respecting that which is different and celebrating that which is the same. As a true anthropologist, Marcia is learning and teaching what is most important, even beautiful, about being human. Thanks Marcia. I will never again think of a Wisconsin with such limiting, narrow bias.

Perhaps you, even as you’re reading this, feel a certain tug to place yourself outside of your comfort zone. Maybe you would like to live in a developing country, serve and be served by the persons you would meet. Perhaps you have a little knowledge of Spanish, or a lot, or you just want the challenge of it all. If this describes you, maybe you should consider volunteering. Give it some serious thought. You can start by looking at the possibilities with Shoulder to Shoulder at https://www.shouldertoshoulder.org/volunteer-opportunities.

Educate a Child and Change the World

November 24, 2014

Shoulder to Shoulder is pleased and proud to introduce the Good Shepherd Bilingual School Sponsorship Program to advance our mission in the frontier region of Intibucá, Honduras.

Why Education?

The river story, often attributed to the social reformer Saul Alinsky, recounts a scene along the banks of a fast moving river. People are drowning and others are jumping into the river to save them. One individual leaves the scene to move upstream. He is initially scolded for abandoning the vital task of saving lives. But, he is actually searching out the source of the problem to learn why and how people are falling into the river in the first place, in order to resolve the issue.

Education in Honduras is certainly an upriver issue. Children are only legally required to go to school through the sixth grade. Public education is free in Honduras. But when you factor in costs of transportation, books and materials, uniforms, and so on, families that can barely feed themselves are greatly burdened by this “free” education. Public education is poorly supported by the Honduran government. Buildings are inadequate and not maintained. Materials are unavailable or offered at a price that students can’t afford. Teachers are ill-prepared. These chronic problems affect all of Honduras, but in the neglected area of the frontier region of Intibucá, they are exacerbated. Children mostly do not continue their education beyond the sixth grade. The economic reality of most families demands that they assist with farm labor or find other low paying employment. Whereas Hondurans with some financial means send their children to quality, private schools, poorer families simply do not have the opportunity.

It is true enough that children are drowning. It is a faulted education system that has tossed them into the river. How many scholars, civil engineers, doctors, physicists, lawyers, artists, musicians, leaders, and visionaries are unknown to Honduras because learning was unavailable to them? It is a sobering thought.

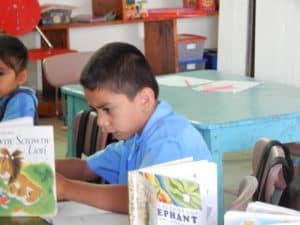

Shoulder to Shoulder is moving upriver. Since its inception, Shoulder to Shoulder has invested in quality education for young people. Our scholarship program enables over one-hundred young people to continue their education beyond the sixth grade, even unto college. The generosity of donors is matched to young people according to merit and need. This is making a substantial difference in their lives individually as well as within the communities they come from and will go to as professionals. In 2012, Shoulder to Shoulder partnered with the Good Shepherd Community of Cincinnati and founded Good Shepherd Bilingual School in Camasca, Intibucá. The building has been erected and three grades (kindergarten, first, and second) are presently enrolled.

The school is public, accessible to everyone, and offers a quality, bilingual education. It is the only one of its kind in all of Honduras. It exists as a collaborative effort among the Honduran Government, the Municipalities of the frontier region of Intibucá, Shoulder to Shoulder, and the students’ parents. Honduras considers it a model for public education. It offers unimagined opportunities for its alumni as well as substantive change for Honduras.

Shoulder to Shoulder believes that you, our donors and benefactors, would like to be part of this historic undertaking. We humbly invite you to seriously consider sponsoring one of the Good Shepherd Bilingual School children. We are certain that this synergetic relationship of generosity and gratitude will be transformative for both you and your sponsored child. Your commitment today will illuminate the path from poverty to progress.

Help us to move up river! www.shouldertoshoulder.org/sponsorshipprogram